Reprinted with permission of the Author.

Was printed in Strange Worlds a toy Collecting Magazine 4 – February 1993

Interview was given via phone, some mistakes are in the text but left as written.

PROFILE:

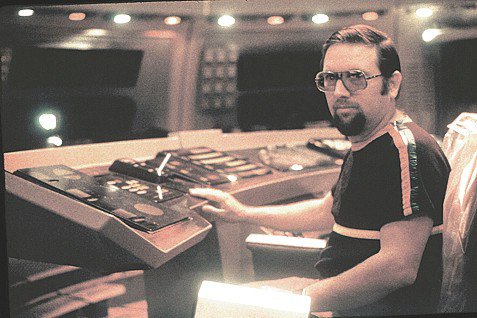

Richard Coyle

Props For The

Final Frontier

by Archie Waugh

MOST “STAR TREK” FANS only dream of being part of science fiction’s most beloved and successful series. For master propmaker Richard Coyle, 44, of Phoenix, Arizona, that dream has been a reality for over ten years. This former television repairman has helped transfer Roddenberry’s television legend to the big screen in four of the “Star Trek” feature films.

Coyle’s personal space odyssey began m 1977 with the premiere of Star Wars. His obsession with this film that redefined big-screen science fiction led him that year to his first convention, the WorldCon in Phoenix.. There he was thrilled to meet and shake hands with his long-time idol Robert Heinlein. Properly hooked, he soon became an active conventioneer. Attired in space-swashbuckler costumes, he often participated in the rowdy gaming that was common at conventions in those days before peace-bonding. Utilizing his background in electronics, he built his own rayguns by taking off-the-shelf toy guns and customizing them with lights and sound effects. The weapons caused such a sensation that he was soon busy filling orders. His work caught the eye of a buyer for a prop company and Coyle soon found himself in Hollywood.

One of his first assigranents was for Star Trek II.- The Wrath of Khan. His job was to modify existing Trek props and to detail new ones. Star Trek II abandoned the bland functionality of Star Trek.TheMotionPicture in favor of more colorful, comic- book-style visuals reminiscent of the TV series. According to Coyle, director Nick Meyer would inspect the set while chomping a ever-present cigar and demanding “more winkie blinkies!”

Coyle was soon busy wiring every hand prop in sight. Sharp eyed viewers can spot examples of his handiwork throughout the film. Coyle constructed Captain Terrell’s wrist-communicator from an off-the-shelf jogging computer. He added lights and a Plexiglas face, then hid the power supply up the actor’s sleeve. “The Enterprise fire extinguishers were commercial ones,” said Coyle. “We dressed them out with acrylic and copper tubing from a refrigerator supply house.” Coyle created the bosun’s whistle used during Spock’s funeral from a G.I. Joe toy accessory.

The scene where McCoy examines Chekov with a medical scanner provided Coyle with a laugh. ‘McCoy is holding [the scanner] upside down,” said Coyle. “I guess I must have designed it wrong, ’cause he’s the doctor!”

When working on predesigned items, Coyle still managed to leave a personal imprint. While detailing the new communicators, Coyle added a button labeled “translock. ” This is a literal reference to a long-stated ability of the ship’s @porter to “lock on’ to a communicator’s signal to locate the persons preparing to beam up.

Coyle enjoyed creating the props, although he was dismayed to see many of his creations end up on the cutting room floor. Unable to convince his employers to let him build science fiction props “on spec,” he went independent. Starting as a subcontractor on Icepirates, he built an impressive resume over the ensuing years. Projects included The Last Starfighter (he made Robert Preston’s communicator from an old Star Trek II medical scanner), Airplane, Radioactive Dreams, “The Powers of Matthew Star,” and “The Greatest American Hero.”

Eventually “Star Trek’ called him again. Coyle cites Star TrekIV- 7he Voyage Home as his favorite experience on the film series. As an independent contractor, Coyle had relatively free run of the Paramount lot. He was the last person photographed in the dilithium chamber where Spock died. After he posed for the photo, the chamber was converted into the Klingon computer room.

Viewers of this film are often unaware that many hand props that Kirk and his Federation renegades use are Klingon devices. The characters supposedly scrounged these Klingon acceswries from the Bird of Prey they captured in the previous film. In Star Trek IV, notice the phaser that Kirk uses to weld the hospital door. It is a Coyle- designed Klingon hand phaser.

Richard Coyle also created Scotty’s lighted clipboard. A beautifully illuminated plexaglass welding device that he created, alas, is visible only briefly in the background of one scene. For the welding visors used by the Vulcan workers seen early in the film Coyle modified the Navy’s gold, high-altitude helmet visors.

One of Coyle’s favorite props for Star Trek IV also became the most frustrating. The script required that the particle collector that Chekov and Uhura take to the aircraft carrier be a blend of Klingon and Federation technology. Coyle constructed a complicated and sturdy device that used an antique, folding flash-camera reflector as an antenna/collector. “Unfortunately, Nimoy rejected the device as too cluttered.” Coyle spent the next two days at Paramount bashing details from the prop with a hammer, a testament to its solid construction.

On Star Trek V. 7he Final Frontier, Coyle worked under model maker Gregory Gein. Mr. Gein had design responsibilities for the film’s models and props. Consequently, Coyle worked on both props and miniatures in this film. Coyle did detailing on the miniature of the Voyager probe seen destroyed by the Klingons early in the film.Many new props were created for Star Trek V. communicators, tricorders, assault rifles, Captain Kirk’s “malfunctioning” logbook pad, and the medical device that Dr. McCoy used on his father.

Coyle laughs when recalling the electronic binoculars that McCoy uses in the film’s Yosemite scene. “Greg Gein brought in these binoculars he had worked up… he had left no room in them for the electronics. I duplicated his design in styrene and packed it full. When Deforest Kelley looks in them, he’s got a 9-volt battery stuck in each eye.”

For the recent Star Trek VI.- The Undiscovered Country, Coyle built new assault phasers, anew bosun’s whistle from Greg Gien’s design, the lighted translators used by Kirk and McCoy in the trial scene, and the Klingon leg irons. The latter were built to Paramount specifications that, according to Coyle, “made no sense. They were way too large. When we sent them down to the set, they were quickly deemed unusable, except for when the shape shifter turns into a little girl and slips out of them. As they had ordered quite a few of these, I got stuck with a lifetime supply of over-sized Klingon leg irons.”

Coyle has mixed feelings about his Hollywood experiences. “There are always frustrations when the prop you worked so hard on ends up virtually invisible on screen.’ Coyle so far has not contributed to “Star Trek: The Next Generation” or “Deep Space Nine.” Paramount’s in-house design team, headed by Michael Okuda and Rick Sternback, produces all the props for the series. No matter what the future brings, chances are good that Richard Coyle will continue making the future tangible for present-day audiences. Trekkers can often find tricorders and phasers made by Coyle for sale at conventions. All his hand-crafted replicas bear his signature and the same quality craftsmanship that he brought to the feature films.