HOLLYWOOD’S FORGOTTEN MAGIC!

PROPS AND THE PEOPLE WHO CREATE THEM

by

Roger Farnham

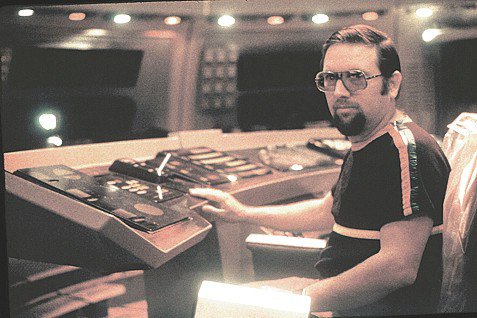

This column is gratefully dedicated to those behind-the-scenes wonder workers, part artist, part technician, and part magician (and badly overworked and underappreciated) who take a piece of metal, a chunk of plastic, an idea, and a lot of talent, and transform it all into that necessary bit of magic that we call a prop.

WHY PROPS?

My love affair with movie props began in the late 1940’s when, as a child, I saw a tiny diorama of the motion picture “One Million Years, B.C.” at the Los Angles Museum. Lying near the diorama, right out where you could touch it (back in those innocent days), was a prop stone ax that had been used in the film. Being a typical kid I had been more interested in the dinosaurs than in the props (in the Raquel Welch version I must admit that I paid more attention to her than to either dinosaurs or props), but even then I felt that there was something special about these often-forgotten bits of movie magic.

As a teenager in the 1950s I spent countless hours watching every science fiction movie that came to my neighborhood theater. One memorable Saturday afternoon they ran the classics “Rocketship XM” and “Destination Moon” as a double feature. It was then that I made an important discovery. It was the first time that I realized just how much the set decorations and props helped to make the story believable.

In “Rocketship XM” the actors sat in standard office chairs and used bits and pieces of “scientific equipment” that had obviously been pressed into service from someplace else. In “Destination Moon” the acceleration couches and control panels looked as if they should be there and, more important, they looked as if they would actually work. That observation forever changed the way I looked at movies and TV.

I have been fortunate enough to meet and get to know many of the best prop makers and I am still amazed at the magic they add to even the most mundane of movies or TV shows. I am even more amazed at the total lack of recognition most of these talented people must put up with.

This column is my way of beginning to thank the many unsung heroes and heroines of the prop-making profession who have added “Phasers”, “Tricorders”, “Communicators”, and “Droids” to our vocabulary, and incalculable enjoyment to our lives.

WHAT IS A PROP?

In the dictionary a prop is described as: 1. To support by placing under or against, 2. To sustain or strengthen, 3. That which supports or holds up something else.

A theatrical prop does just this. It helps to support our sense of reality for the motion picture, TV show, or stage play in which it is used. It helps to sustain our belief in the story and it strengthens our feeling that “this is really happening”.

For example, how convincing would Star Trek be if, instead of Phasers, the Captain and crew used Colt six-shooters ? A good prop seems to belong where it is, doing whatever it does. It is unobtrusive, yet necessary. It heightens the feeling and mood of the piece, yet does not point to itself and say “Hey, look at me.”

In the old stage tradition a prop was called a “property” because it belonged to a theater or traveling group and was used only by that theater or group. Many of the props were generic and could be used for any number of plays. A teapot is a teapot and it makes no difference if it is used in a comedy or a mystery or a drama, it is still a teapot. On the other hand, some props were specifically designed or purchased for a particular show and were used for that show and only for that show.

These items, both generic and special, were cared for by, and were under the control of, the property master. This person, traditionally male, kept things in good repair, made sure each was where it should be before the show began, made sure each was accounted for when the show was over, made sure the “practicals” (props that could actually be used, such as a table lamp) operated, and–most important–built new props as they were needed.

Gradually motion pictures and TV began to replace the stage as the main form of entertainment and this caused some major changes to take place. As unions proliferated and guide lines were established, chairs, tables and teapots were taken away from the prop master and given into the care of the set dresser. Lamps and other electrical equipment came under the control of the electrician. “Gadgets” and special effect items were handled by the special effects department. Over a period of years the prop master became more apt to simply keep track of the props, and less apt to maintain, repair, and build them. About this time the prop making specialist came into being.

The many props that have been designed, built, and used in Star Trek, Star Wars, Ghostbusters, Lost in Space, Alien, Robocop and hundreds of others, all have several things in common: someone decided that a particular item was needed to fill a certain niche, someone designed it, and someone built it.

In most cases the creation of a prop, particularly a prop which is expected to be used more than once, goes through many stages, with many contributors and suggestions, until it finally appears as a finished product.

Exactly what is, and is not, a prop has caused debate for years. For the purposes of this column we have defined a prop as: something that is held, carried, and used by an individual actor. This includes weapons, tools, musical instruments, and a few other items. This DOES NOT include sets, set pieces (control panels, etc.), miniatures, models, or special effects.

WHO BUILT THE FIRST PROPS?

The first props, if they may be so called, were probably the spears and other weapons that primitive man used as a part of their rituals and dances. They help to bring the “spirit” of the hunt or the harvest to the dance or ritual.

The ancient Greeks used the familiar Smiling and Crying masks as props to help convey the feeling of the play to those people who were sitting too far away to see the actor’s faces clearly. These masks, with their overdone expressions, were easily visible at the farthest reaches of the theater. Small megaphones, built into the mouths of the masks, helped to amplify the actor’s voices for those out in the extreme edges of the audience.

Other props probably evolved as the need for them became apparent. The information about what they were, and who built them, is lost in the mists of theatrical history. We have no way of knowing who the first person was who had to build something specifically for a production, rather than using the real thing, but, who ever that person was, they were the first actual propmaker.

Georges Melies was the first film maker who employed specially-built props to any great extent. While most of his props were more in the line of painted theatrical “flats” they still added a huge amount of fun (and a limited amount of believability) to his fantastic movies. His trip to the moon is still a classic example of using props to further the story.

Early science fiction props were often items that were simply bought off-the-shelf and used in a new way. For example, many of Dr. McCoy’s futuristic “instruments” were odd-looking salt and pepper shakers purchased at a local dime store. In other cases the handiest “whatever” was grabbed, modified slightly, and pressed into service. The next time you see the “The Way To Eden” episode of the classic Star Trek, take a close look and you will notice that one of the musical instruments looks suspiciously like a bicycle wheel.

The old TV show “Captain Video” really “wrote the book” on grabbing the nearest item and pressing it into service. The show had the Captain using a standard telephone handset as his “Intergalactic Radio” by holding it by the mouthpiece and speaking into the earpiece. His “Emergency Signal Key” was, as I seem to recall, an office stapler that he pounded on when he needed to send Morse code messages. One episode a fountain pen would be a death ray, and a few episodes later it would be some sort of scientific intstrument.

Many of the early props were designed because either the real thing did not exist (it’s still hard to find a blaster for sale in a local store) or the real thing was not easy to use. For example, a broadsword can weigh up to 16 pounds. A stage sword, on the other hand, is only a light weight 2 or 3 pounds. Much easier and safer to use. Especially by untrained people in the confines of a stage.

THINGS TO COME

In future columns we will be talking to propmakers and designers and bringing you the stories behind the props. We’ll tell you why Lieutenant Worf’s “Bat Leth” had to be redesigned, why some of the props look as they do, and why you never saw TV’s “Batman” take anything out of his utility belt.

In the following months you will find pictures, drawings, and, where possible, scale layouts of your favorite props from all your favorite shows. With each prop will be the story of how it came about, how it evolved and changed, and how it ended up looking and/or working as it finally did. You will also get a chance to learn about the people who labored to “make it so.”

As you read and learn about the effort, talent and, yes, even love, that went into these props I believe that you will join me in thanking the people who have deserved your thanks for many years. Those masters of Hollywood’s forgotten magic—THE PROP MAKERS.

This column Copyright ©1996 by Roger Farnham. All rights reserved. Used with permission.